Posts tagged ‘technology’

Personalized coupons as a vehicle for perfect price discrimination

Given the pervasive tracking and profiling of our shopping and browsing habits, one would expect that retailers would be very good at individualized price discrimination — figuring out what you or I would be willing to pay for an item using data mining, and tailoring prices accordingly. But this doesn’t seem to be happening. Why not?

This mystery isn’t new. Mathematician Andrew Odlyzko predicted a decade ago that data-driven price discrimination would become much more common and effective (paper, interview). Back then, he was far ahead of his time. But today, behavioral advertising at least has gotten good enough that it’s often creepy. The technology works; the impediment to price discrimination lies elsewhere. [1]

It looks like consumers’ perception of unfairness of price discrimination is surprisingly strong, which is why firms balk at overt price discrimination, even though covert price discrimination is all too common. But the covert form of price discrimination is not only less efficient, it also (ironically) has significant social costs — see #3 below for an example. Is there a form of pricing that allows for perfect discrimination (i.e., complete tailoring to individuals), in a way that consumers find acceptable? That would be the holy grail.

In this post, I will argue that the humble coupon, reborn in a high-tech form, could be the solution. Here’s why.

1. Coupons tap into shopper psychology. Customers love them.

Coupons, like sales, introduce unpredictability and rewards into shopping, which provides a tiny dopamine spike that gets us hooked. JC Penney’s recent misadventure in trying to eliminate sales and coupons provides an object lesson:

“It may be a decent deal to buy that item for $5. But for someone like me, who’s always looking for a sale or a coupon — seeing that something is marked down 20 percent off, then being able to hand over the coupon to save, it just entices me. It’s a rush.”

Some startups have exploited this to the hilt, introducing “gamification” into commerce. Shopkick is a prime example. I see this as a very important trend.

2. Coupons aren’t perceived as unfair.

Given the above, shoppers have at best a dim perception of coupons as a price discrimination mechanism. Even when they do, however, coupons aren’t perceived as unfair to nearly the same degree as listing different prices for different consumers, even if the result in either case is identical. [2]

3. Traditional coupons are not personalized.

While customers may have different reasons for liking coupons, from firms’ perspective the way in which traditional coupons aid price discrimination is pretty simple: by forcing customers to waste their time. Econ texts tend to lay it out bluntly. For example, R. Preston McAfee:

Individuals generally value their time at approximately their wages, so that people with low wages, who tend to be the most price-sensitive, also have the lowest value of time. … A thrifty shopper may be able to spend an hour sorting through the coupons in the newspaper and save $20 on a $200 shopping expedition … This is a good deal for a consumer who values time at less than $20 per hour, and a bad deal for the consumer that values time in excess of $20 per hour. Thus, relatively poor consumers choose to use coupons, which permits the seller to have a price cut that is approximately targeted at the more price-sensitive group.

Clearly, for this to be effective, coupon redemption must be deliberately made time-consuming.

To the extent that there is coupon personalization, it seems to be for changing shopper behavior (e.g., getting them to try out a new product) rather than a pricing mechanism. The NYT story from last year about Target targeting pregnant women falls into this category. That said, these different forms of personalization aren’t entirely distinct, which is a point I will return to in a later article.

4. The traditional model doesn’t work well any more.

Paper coupons have a limited future. As for digital coupons, there is a natural progression toward interfaces that make it easier to acquire and redeem them. In particular, as more shoppers start to pay using their phones in stores, I anticipate coupon redemption being integrated into payment apps, thus becoming almost frictionless.

An interesting side-effect of smartphone-based coupon redemption is that it gives the shopper more privacy, avoiding the awkwardness of pulling out coupons from a purse or wallet. This will further open up coupons to a wealthier demographic, making them even less effective at discriminating between wealthier shoppers and less affluent ones.

5. The coupon is being reborn in a data-driven, personalized form.

With behavioral profiling, companies can determine how much a consumer will pay for a product, and deliver coupons selectively so that each customer’s discount reflects what they are willing to pay. They key difference is what while in the past, customers decided whether or not to look for, collect, and use a coupon, in the new model companies will determine who gets which coupons.

In the extreme, coupons will be available for all purchases, and smart shopping software on our phones or browsers will automatically search, aggregate, manage, and redeem these coupons, showing coupon-adjusted prices when browsing for products. More realistically, the process won’t be completely frictionless, since that would lose the psychological benefit. Coupons will probably also merge with “rewards,” “points,” discounts, and various other incentives.

There have been rumblings of this shift here and there for a few years now, and it seems to be happening gradually. Google’s acquisition of Incentive Targeting a few months ago seems significant, and at the very least demonstrates that tech companies are eyeing this space as well, and not just retailers. As digital feudalism takes root, it could accelerate the trend of individualized shopping experiences.

In summary, personalized coupons offer a vehicle for realizing the full potential of data mining for commerce by tailoring prices in a way that consumers seem to find acceptable. Neither coupons nor price discrimination should be viewed in isolation — together with rewards and various other incentive schemes, they are part of the trend of individualized, data mining-driven commerce that’s here to stay.

Footnotes

[1] Since I’m eschewing some academic terminology in this post, here are a few references and points of clarification. My interest is in first-degree price discrimination. Any price discrimination requires market power; my assumption is that is the case in practice because competition is always imperfect, and we should expect quite a bit of first-degree price discrimination. The observed level is puzzlingly low.

The impact of technology on the ability to personalize prices is complex, and behavioral profiling is only one aspect. Technology also makes competition less perfect by allowing firms to customize products to a greater degree, so that there are no exact substitutes. Finally, technology hinders first-degree price discrimination to an extent by allowing consumers to compare prices between different retailers more easily. The interaction between these effects is analyzed in this paper.

Technology also increases the incentive to price discriminate. As production becomes more and more automated, marginal costs drop relative to fixed costs. In the extreme, digital goods have essentially zero marginal cost. When marginal production costs are low, firms will try to tailor prices since any sale above marginal cost increases profits.

My use of the terms overt and covert is rooted in the theory of price fairness in psychology and behavioral economics, and relates to the presentation of the transaction. While it is somewhat related to first- vs. second/third-degree price discrimination, it is better understood as a separate axis, one that is not captured by theories of rational firms and consumers.

[2] An exception is when non-coupon customers are made aware that others are getting a better deal. This happens, for example, when there is a prominent coupon-code form field in an online shopping checkout flow. See here for a study.

Thanks to Sebastian Gold for reviewing a draft, and to Justin Brickell for interesting conversations that led me to this line of thinking.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter or Google+.

In Silicon Valley, Great Power but No Responsibility

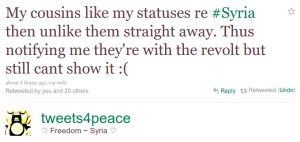

I saw a tweet today that gave me a lot to think about:

.

A rather intricate example of social adaptation to technology. If I understand correctly, the cousins in question are taking advantage of the fact that liking someone’s status/post on Facebook generates a notification for the poster that remains even if the post is immediately unliked. [1]

What’s humbling is that such minor features have the power to affect so many, and so profoundly. What’s scary is that the feature is so fickle. If Facebook starts making updates available through a real-time API, like Google Buzz does, then the ‘like’ will stick around forever on some external site and users will be none the wiser until something goes wrong. Similar things have happened: a woman was fired because sensitive information she put on Twitter and then deleted was cached by an external site. I’ve written about the privacy dangers of making public data “more public”, including the problems of real-time APIs. [2]

As complex and fascinating as the technical issues are, the moral challenges interest me more. We’re at a unique time in history in terms of technologists having so much direct power. There’s just something about the picture of an engineer in Silicon Valley pushing a feature live at the end of a week, and then heading out for some beer, while people halfway around the world wake up and start using the feature and trusting their lives to it. It gives you pause.

This isn’t just about privacy or just about people in oppressed countries. RescueTime estimates that 5.3 million hours were spent worldwide on Google’s Les Paul doodle feature. Was that a net social good? Who is making the call? Google has an insanely rigorous A/B testing process to optimize between 41 shades of blue, but do they have any kind of process in place to decide whether to release a feature that 5.3 million hours—eight lifetimes—are spent on?

For the first time in history, the impact of technology is being felt worldwide and at Internet speed. The magic of automation and ‘scale’ dramatically magnifies effort and thus bestows great power upon developers, but it also comes with the burden of social responsibility. Technologists have always been able to rely on someone else to make the moral decisions. But not anymore—there is no ‘chain of command,’ and the law is far too slow to have anything to say most of the time. Inevitably, engineers have to learn to incorporate social costs and benefits into the decision-making process.

Many people have been raising awareness of this—danah boyd often talks about how tech products make a mess of many things: privacy for one, but social nuances in general. And recently at TEDxSiliconValley, Damon Horowitz argued that technologists need a moral code.

But here’s the thing—and this is probably going to infuriate some of you—I fear that these appeals are falling on deaf ears. Hackers build things because it’s fun; we see ourselves as twiddling bits on our computers, and generally don’t even contemplate, let alone internalize, the far-away consequences of our actions. Privacy is viewed in oversimplified access-control terms and there isn’t even a vocabulary for a lot of the nuances that users expect.

The ignorant are at least teachable, but I often hear a willful disdain for moral issues. Anything that’s technically feasible is seen as fair game and those who raise objections are seen as incompetent outsiders trying to rain on the parade of techno-utopia. The pronouncements of executives like Schmidt and Zuckerberg, not to mention the writings of people like Arrington and Scoble who in many ways define the Valley culture, reflect a tone-deaf thinking and a we-make-the-rules-get-over-it attitude.

Something’s gotta give.

[1] It’s possible that the poster is talking about Twitter, and by ‘like’ they mean ‘favorite’. This makes no difference to the rest of my arguments; if anything it’s stronger because Twitter already has a Firehose.

[2] Potential bugs are another reason that this feature is fickle. As techies might recognize, ensuring that a like doesn’t show up after an item is unliked maps to the problem of update propagation in a distributed database, which the CAP theorem proves is hard. Indeed, Facebook often has glitches of exactly this sort—you might notice it because a comment notification shows up and the comment doesn’t, or vice versa, or different people see different like counts, etc.

[ETA] I see this essay as somewhat complementary to my last one on how information technology enables us to be more private contrasted with the ways in which it also enables us to publicize our lives. There I talked about the role of consumers of technology in determining its direction; this article is about the role of the creators.

[Edit 2] Changed the British spelling ‘wilful’ to American.

Thanks to Jonathan Mayer for comments on a draft.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter.

Bad Internet Law: What Techies Can Do About It

The bad news is that fighting specific laws as they come up is an uphill battle. What has changed in the last ten years is that the Internet has thoroughly permeated society, and therefore the interest groups pushing these laws are much more determined to get their way. The good news is that lawmakers are reasonably receptive to arguments from both sides. So far, however, they are not hearing nearly enough of our side of the story. It’s time for techies to step up and get more actively involved in policy if we hope to preserve what we’ve come to see as our way of life. Here’s how you can make a difference.

1. Stick to your strengths—explain technology. The primary reason why Washington is prone to making bad tech law is that they don’t understand tech, and don’t understand how bits are different from atoms. Not only is educating policymakers on tech more effective, as a technologist you’ll have more credibility if you stick to doing that, rather than opining on specific policy measures.

2. Don’t go it alone. Giving equal weight to every citizen’s input on individual issues may or may not be a good idea in theory, but it certainly doesn’t work that way in practice. Money, expertise, connections and familiarity with the system all count. You’ll find it much easier to be heard and to make a difference if you combine your efforts with an existing tech policy group. You’ll also learn the ropes much more quickly by networking. Organizations like the EFF are always looking for help from outside technologists.

3. Charity begins at home—talk to your policy people. If you work at a large tech company, you’re already in a great position: your company has a policy group, a.k.a. lobbyists. Help them with their understanding of tech and business constraints, and have them explain the policy issues they’re involved in. Engineers often view the in-house policy and legal groups as a bunch of lawyers trying to impose arbitrary rules. This attitude hurts in the long run.

4. Learn to navigate the Three Letter Agencies. “The Government” is not a monolithic entity. To a first approximation there are the two Houses, a variety of Agencies, Departments and Commissions, the state legislatures and the state Attorneys General. They differ in their responsibilities, agendas, means of citizen participation and the receptiveness to input on technology. It can be bewildering at first but don’t worry too much about it; you can pick it up as you go along. Weird but true: most Internet issues in the House are handled by the “Energy and Commerce” subcommittee!

While I have focused on bad Internet laws, since that is where the tech/politics disconnect is most obvious, there are certainly many laws and regulations that have a largely positive, or at least a mixed reception in technology circles. Net neutrality is a prominent example; I am myself involved in the Do Not Track project. These are good opportunities to get involved as well, since there is always a shortage of technical folks. I would suggest picking one or two issues, even though it might be tempting to speak out about everything you have an opinion on.

To those of you who are about to post something like, “What’s the point? Congresspeople are all bought and paid for and aren’t going to listen to us anyway,” I have two things to say:

- Tech policy is certainly hard because of the huge chasm, but cynicism is unwarranted. Lawmakers are willing to listen and you will have an impact if you stick with it.

- If you’re not interested, that’s your prerogative. But please refrain from discouraging others who’re fighting for your rights. Defeatism and apathy are part of the problem.

Finally, here are some tech policy blogs and resources if you feel like “lurking” before you’re ready to jump in.

Google Buzz, Social Norms and Privacy

Another day, another privacy backlash — this time with Google Buzz. What’s new? Lots, as it turns out.

There are many minor ways in which Google Buzz fails, both with regard to privacy and otherwise. For example, I’ve been posting my Buzz updates publicly because the user interface for posting it to a restricted group is horribly clunky. (Post only to my followers? What’s the point of that, when anyone can start following me?! Make it easy to post to a group that I have control over!)

But the major privacy SNAFU, as you’ve probably heard, is auto-follow. Google automatically makes public a list of the top 25 or so people you’ve corresponded with in Gmail or Google talk. Worse, the button to turn this “feature” off resides in your Google-wide profile, making it unnecessarily hard to find because it isn’t within the Buzz interface itself.

This is a classic example of what happens when the user interface is created by programmers instead of designers, a recurring problem for Google. Programmers partition features in a way that fits the computer’s natural data model, rather than the user’s natural mental model.

But getting back to privacy, it is a certainty in a statistical sense that Google outed a few affairs and other secret relationships. For even if you were yourself savvy enough to turn off the public display of your top correspondents, there’s a good chance the other party wasn’t, and might not have turned it off on their end.

When I enabled Buzz and realized what had happened, something changed for me in my head. I’d always regarded email and chat as a private medium. But that’s not true any more; Google forced me to discard my earlier expectations. Even if Google apologizes and retracts auto-follow (not that I think that’s likely), the way I view email has permanently changed, because I can’t be sure that it won’t happen again. I lost some of the privacy expectation that I had of not only Google’s services, but of email and chat in general, albeit to a lesser extent.

What I’ve tried to do in the preceding paragraphs is show in a step-by-step manner how Google’s move changed social norms. The larger players like Google and Microsoft have been very conservative when it comes to privacy, unlike upstarts like Facebook. So why did Google enable auto-follow? By all accounts, their hand was forced: they needed a social network to compete with Facebook and Twitter. Given the head-start that their competitors have, the only real way to compete was to drag their users into participating.

Google ended up changing society’s norms in a detrimental way in order to meet their business objectives. This has become a recurring theme (c.f. the section on Facebook in that article). I don’t think there is any possibility of putting the genie back in the bottle; this trend will only continue. This time it was about who I email; soon my expectations about the contents of emails themselves will probably change.

I believe that in the long run, the only “stable equilibrium” of privacy norms, as it were, would be for everyone to simply assume that everything they type into a computer will be publicly visible either instantly or at some point in the future, outside their control. That is not necessarily as terrible as it may seem. Nonetheless, society will take a long time to get there. Until then, the best we can do is push back against intrusions as much as possible, delaying the inevitable, giving ourselves enough time to adapt.

Do your part to fight back against auto-follow. Let Google know how you feel. Blog about it or leave a comment.

Updates

- A New York Times blogger picked up the controversy.

- Joe Bonneau has an analysis of users’ confused reactions.

- Google has announced that it is rolling out some user-interface changes in response to the feedback. That is better than before, but the default is still public auto-follow.

- The horror stories due to auto-follow have begun.

- I have a new article with advice on privacy-conscious design.

- Google decided to nix auto-follow after all! Awesome.

Thanks to Joe Bonneau for reviewing a draft of this article.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter.