Posts tagged ‘Google’

Google+ and Privacy: A Roundup

By all accounts, Google has done a great job with Plus, both on privacy and on the closely related goal of better capturing real-life social nuances. [1] This article will summarize the privacy discussions I’ve had in the first few days of using the service and the news I’ve come across.

The origin of Circles

“Circles,” as you’re probably aware, is the big privacy-enhancing feature. A presentation titled “The Real-Life Social Network” by user-experience designer Paul Adams almost exactly a year ago went viral in the tech community; it looks likely this was the genesis, or at least a crystallization, of the Circles concept.

But Adams defected to Facebook a few months later, which lead to speculation that it was the end of whatever plans Google may have had for the concept. But little did the world know at the time that Plus was a company-wide, bet-the-farm initiative involving 30 product teams and hundreds of engineers, and that the departure of one made no difference.

Meanwhile, Facebook introduced a friend-lists feature but it was DOA. When you’re staring at a giant list of several hundred “friends” — Facebook doesn’t do a good job of discouraging indiscriminate friending — categorizing them all is intimidating to say the least. My guess is that Facebook was merely playing the privacy communication game.

Why are circles effective?

I did an informal poll to see if people are taking advantage of Circles to organize their friend groups. Admittedly, I was looking at a tech-savvy, privacy-conscious group of users, but the response was overwhelming, and it was enough to convince me that Circles will be a success. There’s a lot of excitement among the early user community as they collectively figure out the technology as well as the norms and best practices for Circles. For example, this tip on how to copy a circle has been shared over 400 times as I write this.

One obvious explanation is that Circles captures real-life boundaries, and this is what users have been waiting for all along. That’s no doubt true, but I think there’s more to it than that. Multiple people have pointed out how the exemplary user interface for creating circles encouraged them to explore the feature. It is gratifying to see that Google has finally learned the importance of interface and interaction design in getting social right.

There are several other UI features that contribute to the success of Circles. When friending someone, you’re forced to pick one or more circles, instead of being allowed to drop them into a generic bucket and categorize them later. But in spite of this, the UI is so good that I find it no harder than friending on Facebook.

In addition, you have to pick circles to share each post with (but again the interface makes it really easy). Finally, each post has a little snippet that shows who can see it, which has the effect of constantly reminding you to mind the information flow. In short, it is nearly impossible to ignore the Circles paradigm.

The resharing bug

Google+ tries to balance privacy with Twitter-like resharing, which is always going to be tricky. Amusing inconsistencies result if you share a post with a circle that doesn’t include the original poster. A more serious issue, pointed out by many people including an FT blogger, is that “limited” posts can be publicly reshared. To their credit, Google engineers acknowledged it and quickly disabled the feature.

Meanwhile, some have opined that this issue is “totally bogus” and that this is how life works and how email works, in that when you tell someone a secret, they could share it with others. I strongly disagree, for two reasons.

First, this is not how the real world (or even email) works. Someone can repeat a secret you told them in real life, or forward an email, but they typically won’t broadcast it to the whole world. We’re talking about making something public here, something that will be forever associated with your real name and could very well come up in a web search.

Second, user-interface hints are an important and well-established way of nudging privacy-impacting behaviors. If there’s a ‘share’ button with a ‘public’ setting, many users will assume that it is OK to do just that. Twitter used to allow public retweets of protected tweets, and a study found that this had been done millions of times. In response, Twitter removed this ability. The privicons project seeks to embed similar hints in emails.

In other words, the privacy skeptics are missing the point: the goal of the feature is not to try to technologically prevent leakage of protected information, but to better communicate to users what’s OK to share and what isn’t. And in this case, the simplest way to do that is to remove the 1-click ability to share protected content publicly, and instead let users copy-paste if they really want to do that. It would also make sense to remind users to be careful when they’re sharing a limited to their circles, which, I’m happy to see, is exactly what Google is doing.

The tip you now see when you share a limited post (with another limited group). This is my favorite Google+ feature.

A window into your circles

Paul Ohm points out that if someone shares content with a set of circles that includes you, you get to see 21 users who are part of those circles, apparently picked at random. [2] This means that if you look at these lists of 21 over time you can figure out a lot about someone’s circles, and possibly decipher them completely. Note that by default your profile shows a list of users in your circles, but not who’s in which circle, which for most people is significantly more sensitive.

In my view, this is an interesting finding, but not anything Google needs to fix; the feature is very useful (and arguably privacy-enhancing) and the information leakage is an inevitable tradeoff. But it’s definitely something that users would do well to be aware of: the secrecy of your circles is far from bulletproof.

Speaking of which, the network visibility of different users on their profile page confused me terribly, until I realized Google+ is A/B testing that privacy setting! These are the two possibilities you could see when you edit your profile and click the circles area in the left sidebar: A, B. This is very interesting and unusual. At any rate, very few users seem to have changed the defaults so far, based on a random sample of a few dozen profiles.

Identity and distributed social networking

Some people are peeved that Google+ discourages you from participating pseudonymously. I don’t think a social network that wants to target the mainstream and wants to capture real-world relationships has any real choice about this. In fact, I want it to go further. Right now, Google+ often suggests I add someone I’ve already added, which turns out to be because I’ve corresponded with multiple email addresses belonging to that person. Such user confusion could be minimized if the system did some graph-mining to automatically figure out which identities belong to the same person. [3]

A related question is what this will mean for distributed social networking, which was hailed a year ago as the savior of privacy and user control. My guess is that Google+ will take the wind out of it — Google takeout gives you a significant degree of control over your data. Further, due to the Apple-Twitter integration and the success of Android, the threat of Facebook monopolizing identities has been obliterated; there are at least three strong players now.

Another reason why Google+ competes with distributed social networks: for people worried about the social networking service provider (or the Government) reading their posts, client-side encryption on top of Google+ could work. The Circles feature is exactly what is needed to make encrypted posts viable, because you can make a circle of those who are using a compatible encryption/decryption plugin. At least a half-dozen such plugins have been created over the years (examples: 1, 2), but it doesn’t make much sense to use these over Facebook or Twitter. Once the Google+ developer API rolls out, I’m sure we’ll see yet another avatar of the encrypted status message idea, and perhaps the the n-th time will be the charm.

Concluding thoughts

Two years ago, I wrote that there’s a market case for a privacy-respecting social network to fill Livejournal’s shoes. Google+ seems poised to fulfill most of what I anticipated in that essay; the asymmetric nature of relationships and the ability to present different facets of one’s life to different people are two important characteristics that the two social networks have in common. [4]

Many have speculated on whether, and to what extent, Google+ is a threat to Facebook. One recurring comparison is Facebook as “ghetto” compared to Plus, such as in this image making the rounds on Reddit, reminiscent of Facebook vs. Myspace a few years ago. This perception of “coolness” and “class” is the single biggest thing Google+ has got going for it, more than any technological feature.

It’s funny how people see different things in Google+. While I’m planning to use Google+ as a Livejournal replacement for protected posts, since that’s what fits my needs, the majority of the commentary has compared it to Facebook. A few think it could replace Twitter, generalizing from their own corner of the Google+ network where people haven’t been using the privacy options. Forbes, being a business publication, thinks LinkedIn is the target. I’ve seen a couple of commenters saying they might use it instead of Yammer, another business tool. According to yet other articles, Flickr, Skype and various other Internet companies should be shaking in their boots. Have you heard the parable of the blind men and the elephant?

In short, Google+ is whatever you want it to be, and probably a better version of it. It’s remarkable that they’ve pulled this off without making it a confusing, bloated mess. Myspace founder Tom Anderson seems to have the most sensible view so far: Google+ is simply a better … Google, in that the company now has a smoother, more integrated set of services. You’d think people would have figured it out from the name!

[1] I will use the term “privacy” in this article to encompass both senses.

[2] It’s actually 22 users, including yourself and the poster. It’s not clear just how random the list is; in my perusal, mutual friends seem to be preferentially picked.

[3] I am not suggesting that Google+ should prevent users from having multiple accounts, although Circles makes it much less useful/necessary to have multiple accounts.

[4] On the other hand, when it comes to third party data collection, I do not believe that the market can fix itself.

I’m grateful to Joe Hall, Jonathan Mayer, and many, many others with whom I had interesting discussions, mostly via Google+ itself, on the topics that led to this post.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter or Google+.

Google Docs Identity Leak Bug Fixed

Yesterday I wrote about a bug in Google Docs that lets an arbitrary website find your identity. This morning I woke up to this piece of good news in my Inbox:

The fix is pushed out and live for all users as of the middle of last night. Basically we only show the username of collaborators if they are explicitly listed on the ACL of the spreadsheet. Otherwise we call them “Anonymous user”. This means that an editor of the document had to already know the username in order for that username to be visible to collaborators.

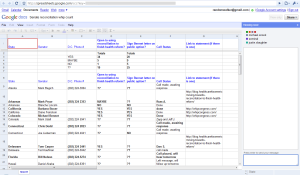

I can confirm that the demo page no longer finds my identity. And the spreadsheet in my last post now looks like this:

The Google Docs help question “Collaborating: Why are some users anonymous?” explains:

If a document is set by the owner to be viewable or editable by everyone, then Google Docs does not show the names of those who choose to view or edit the document. Google Docs displays only the identities of users who are explicitly given permission to view or edit a document (either individually or as part of a group).

You might wonder what happens if the attacker explicitly gives permission to a whole bunch of users (say using scraped email addresses) . There seems to be an extra level of protection now:

Sounds like a happy resolution.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter.

How Google Docs Leaks Your Identity

Recap. In the previous two articles in this Ubercookies series, I showed how an arbitrary website that you visit can learn your identity using the “history stealing” bug in web browsers. In this article I will show how a bug in Google Docs gives any website the same capability in a far easier manner.

Update. A Google Docs team member tells me that a fix should be live later today.

Update 2. Now fixed.

About six weeks ago I discovered that a feature/bug in Google docs can be used to mass harvest e-mail addresses. I noted it in my journal, but soon afterwards I realized that it was much worse: you could actually discover the identity of web visitors using the bug. Recently, Vincent Toubiana and I implemented the attack; here is a video of the demo webpage (on my domain, in no way related to Google) just to show that we got it working.

(You might need to hit pause to read the text.)

I’m not releasing the live demo, since the vulnerability unfortunately still exists (more on this below). Let us now study the attack in more detail.

Bug or feature? Google Spreadsheets has a feature that tells you who else is editing the document. It’s actually really nifty: you can see in real time who is editing which cell, and it even seems to have live chat. The problem is that this feature is available even for publicly viewable documents. Do you see where this is going?

First of all, this is a problem even without the surreptitious use I’m going to describe. Here’s a public spreadsheet I found with 10 seconds of Googling that a few people seem to be viewing when I looked. I’m not sure the author of this document intended it to be publicly viewable or editable.

The attack works by embedding an invisible iframe (dimensions 0x0) into the malicious web page. The iframe loads a public spreadsheet that the attacker has already created. In a separate backend process, the attacker constantly checks the list of people viewing the spreadsheet and records this information. After the iframe is embedded, the Javascript on the page page waits a second or two and queries the attacker’s server to get the username of the user who most recently appeared on the list.

What if multiple people are visiting the page at roughly the same time? It’s not a problem, for two reasons: 1. Google Spreadsheets has a “push” notification system for updating the frontend which enables the attacker to get the identity of the new user virtually instantaneously. 2. To further increase accuracy, the attacker can create (say) 10 spreadsheets and embed a random subset of 5 into any given visitor’s page, making it exceptionally unlikely that there will be a collision.

The only inefficient part of the attack as Toubiana and I have implemented it is that it requires a browser (with a GUI) to be open to monitor the spreadsheet. Browser rendering engines have been modularized into scriptable components, so with a little more effort it should be possible to run this without a display. At present I have it running out of an old laptop tucked away in my dresser :-)

Defense. How can Google fix this bug? There are stop-gap measures, but as far as I can see the only real solution is to disable the collaborator list for public documents. Again a trade-off between functionality and privacy as we saw in the previous article.

Many people responded to my original post saying they were going to stay logged out of Google when they didn’t need to be logged in (since you can’t log out of just Google Docs separately). Unfortunately, that’s not a feasible solution for me, and I suspect many other people. There are at least 3 Google services that I constantly need to keep tabs on; otherwise my entire workflow would come to a screeching halt. So I just have to wait for Google to do something about this bug. Which brings me to my next point:

Great power, great responsibility. There is a huge commercial benefit to becoming an identity provider. As Michael Arrington has repeatedly noted, many Internet companies issue OpenIDs but don’t accept them from other providers, in a race to “own the identity” of as many users as possible. That is of course business as usual, but the players in this race need to wake up to the fact that being an identity provider is asking users for a great deal of trust, whether or not users realize it.

An identity-stealing bug is an (unintentional) violation of that trust because — among many other reasons — it is a precursor to stealing your actual account credentials. (That is particularly scary with Google due to their lack of anything resembling customer service for account issues.) One strategy for stealing account credentials is a phishing page mimicking the Google login page, with your username filled in. Users are much less likely to be suspicious and more likely to respond to messages that have their name on them. Research on social phishing reaches similar conclusions.

I’ve been in contact with people at Google about this bug and I’ve been told a fix is being worked on, specifically that “less presence information will be revealed.” I take it to mean the attack described here won’t work. Since they are making a good-faith effort to fix it, I’m not releasing the demo itself. It has been a long time, though. The Buzz privacy issues were fixed in 4 days, and that kind of urgency is necessary for security issues of this magnitude.

A kind of request forgery. The attack here can be seen as a simpleminded cross-site request forgery. In general, any type of request forgery bug that causes your browser to initiate a publicly recorded interaction on your behalf will immediately leak you identity. For example, if (hypothetically) visiting a URL causes your browser to leave a comment on a specific Youtube video, then the attacker can create a Youtube video and constantly monitor it for comments, mirroring the attack technique used here.

Another technical lesson from this bug is that access control in social networking can be tricky. I’ve written before that privacy in social networking is about a lot more than access control, and that theory doesn’t help determine user reactions to your product. But this bug was an access control issue, and theory would have helped. Websites designing social features would do well to have someone with an academic background thinking about security issues.

Up next. In this post as well as the previous ones, I’ve briefly hinted at what exactly can go wrong if websites can learn your identity. The next post in this series will examine that issue in more detail. Stay tuned — it turns out there’s quite a bit more to say about that, and you might be surprised.

Thanks to Vincent Toubiana for reviewing a draft.

To stay on top of future posts, subscribe to the RSS feed or follow me on Twitter.